Techniques for distant terrain

There's a lot of work that goes into making a good-looking landscape for a game. I've been working on Fall of an Empire for a while, and since the game uses an overworld similar to Total War, Civilization or Mount and Blade the map is made entirely of distant terrain. Here are the techniques I use to build the FOAE map. Although FOAE is a strategy game with an RTS-style camera, these techniques can also be used for anything that has a landscape in it.

Detail levels

When we look at an object from different distances we make out different levels of detail. For instance, looking at a wall from a distance it might look like a blank white box, if we get closer we can see scratches and damage and up close we can see the fine rough detail of the paint. This is the same for landscapes. Up close we can see individual pebbles, blades of grass and sticks. Further away we see variation in the types of grass, darker and lighter areas and even further away we can only see that macro-level variation.

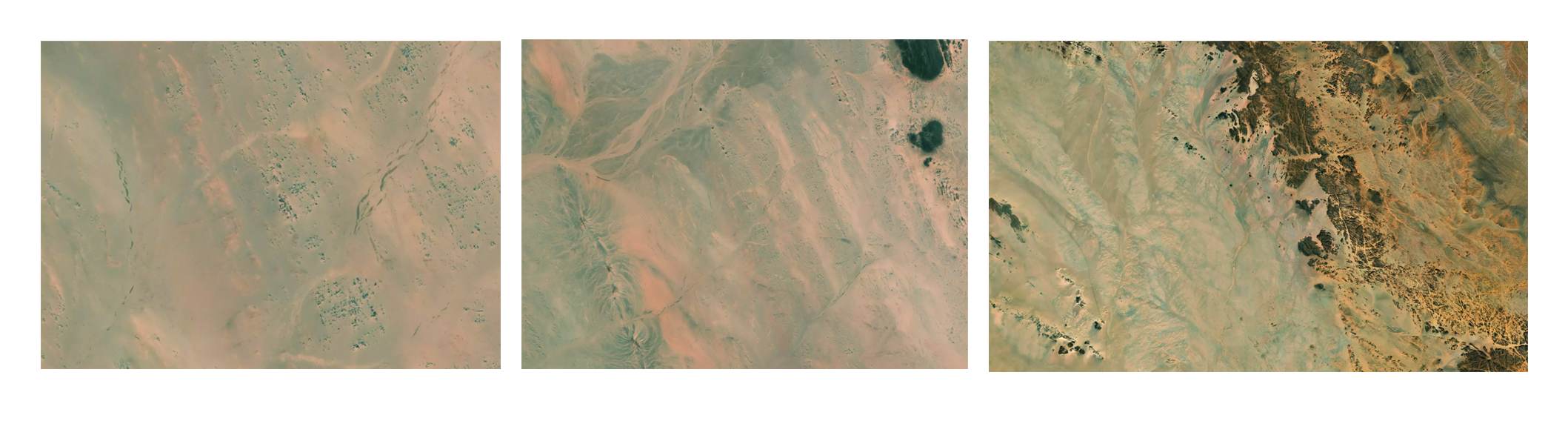

To replicate this effect in a game, we can have three texture detail levels. One is the closest (for instance, a grass texture) and repeated at about every meter. Then on top of that we can layer a larger grass texture every 100m. Finally, we can layer a texture that covers the entire terrain. We can use something like Gaea or World Machine to generate this texture, since they allow us to easily take into account things like erosion and landscape protrusions.

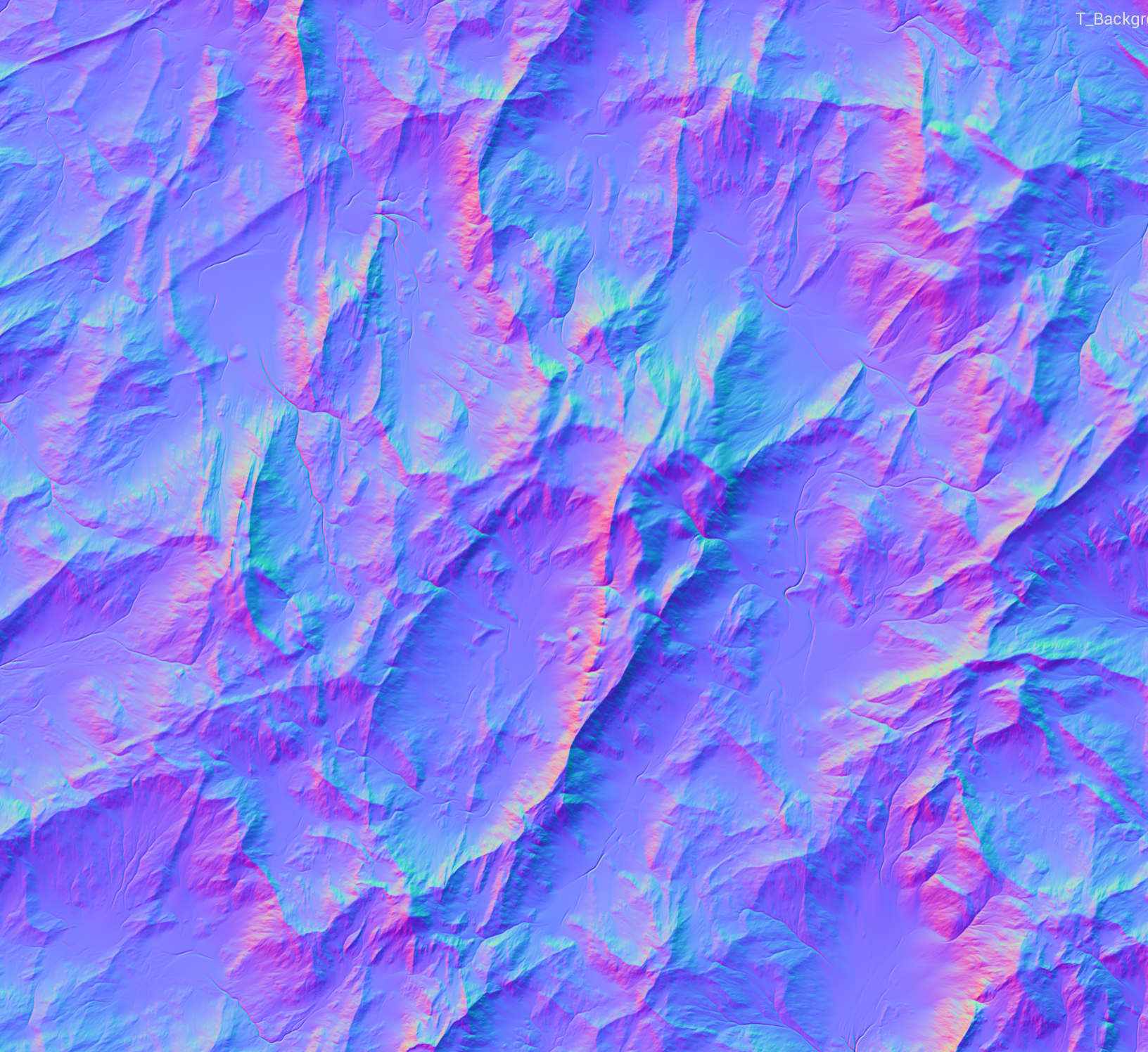

Whole-terrain normals

This texture variation isn't just for diffuse textures. You can also create a normal texture that covers the entire landscape using your terrain tool. If you've created your terrain entirely within some landscape tool you can simply export the normal map, which will look something like this.

Otherwise, if you've made your landscape in the game engine you can import it into your terrain tool, run it through a minor erosion pass and then export it back out. Don't give it too much erosion though or the normals won't match up with the actual landscape in the game.

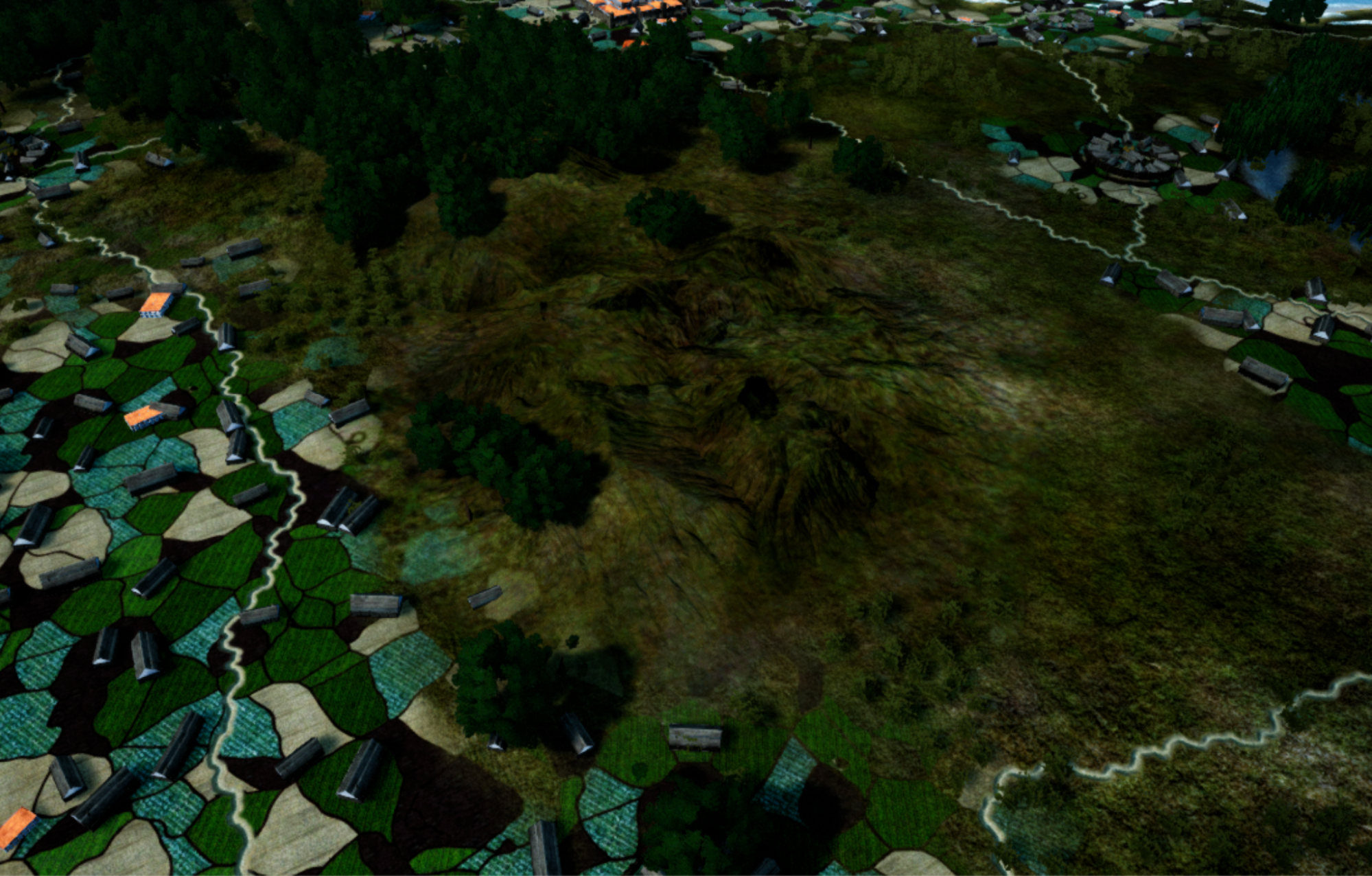

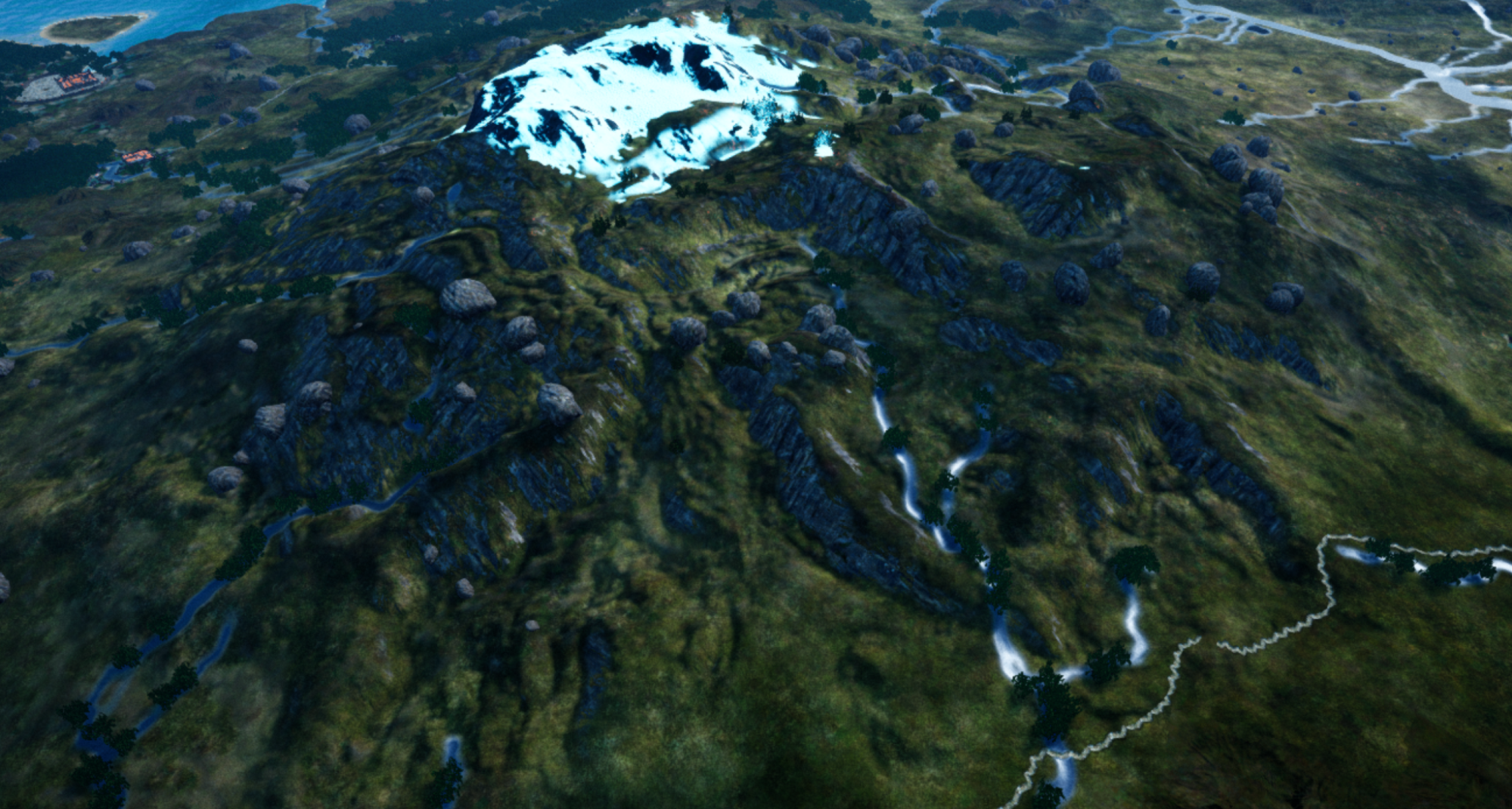

As we can see before adding the normal map, it looks quite flat - everything is lit similarly.

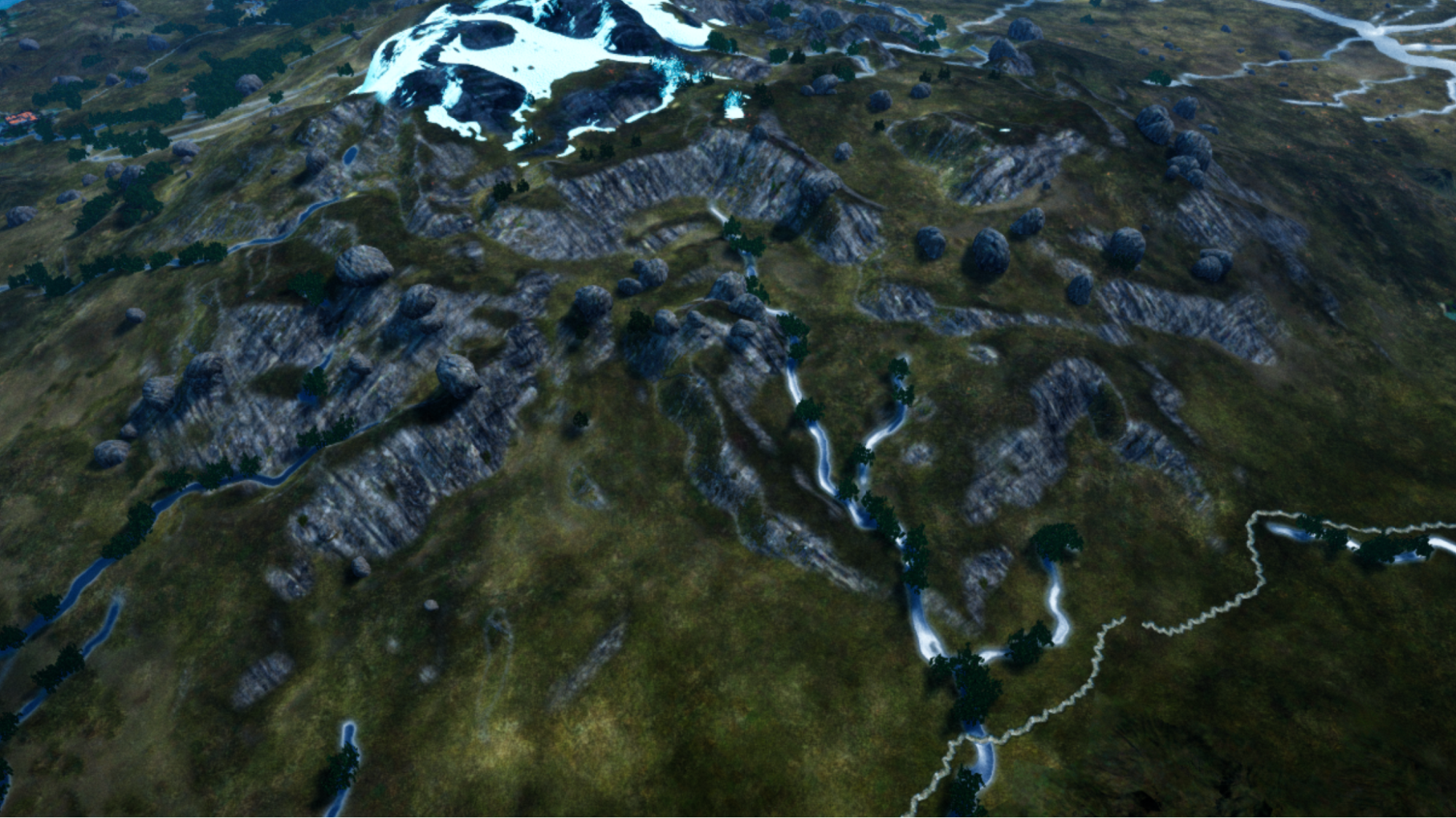

And then when we add the normal map, it's much more detailed, you can see all the nooks and crevices on the terrain.

Underwater details

Adding details to the underwater parts of your map can be a good way to make it look more lively - even if the camera itself never goes under the water.

For instance, here's the ocean before - anything close to or under the water is just sand. However, if you look at a beach from above you'll see that while there is sand, there are rocky outcrops, kelp forests, mussels beds and other features that break it up.

Here's what that looks like when we alter our landscape material so that it has patches of gravel (added via blending with the sand using a noise texture) and adding kelp forests and rock clumps using the Unreal Engine grass tool.

To make it even more visually interesting, you can add schools of fish using particle effects and other doodads on the seafloor.

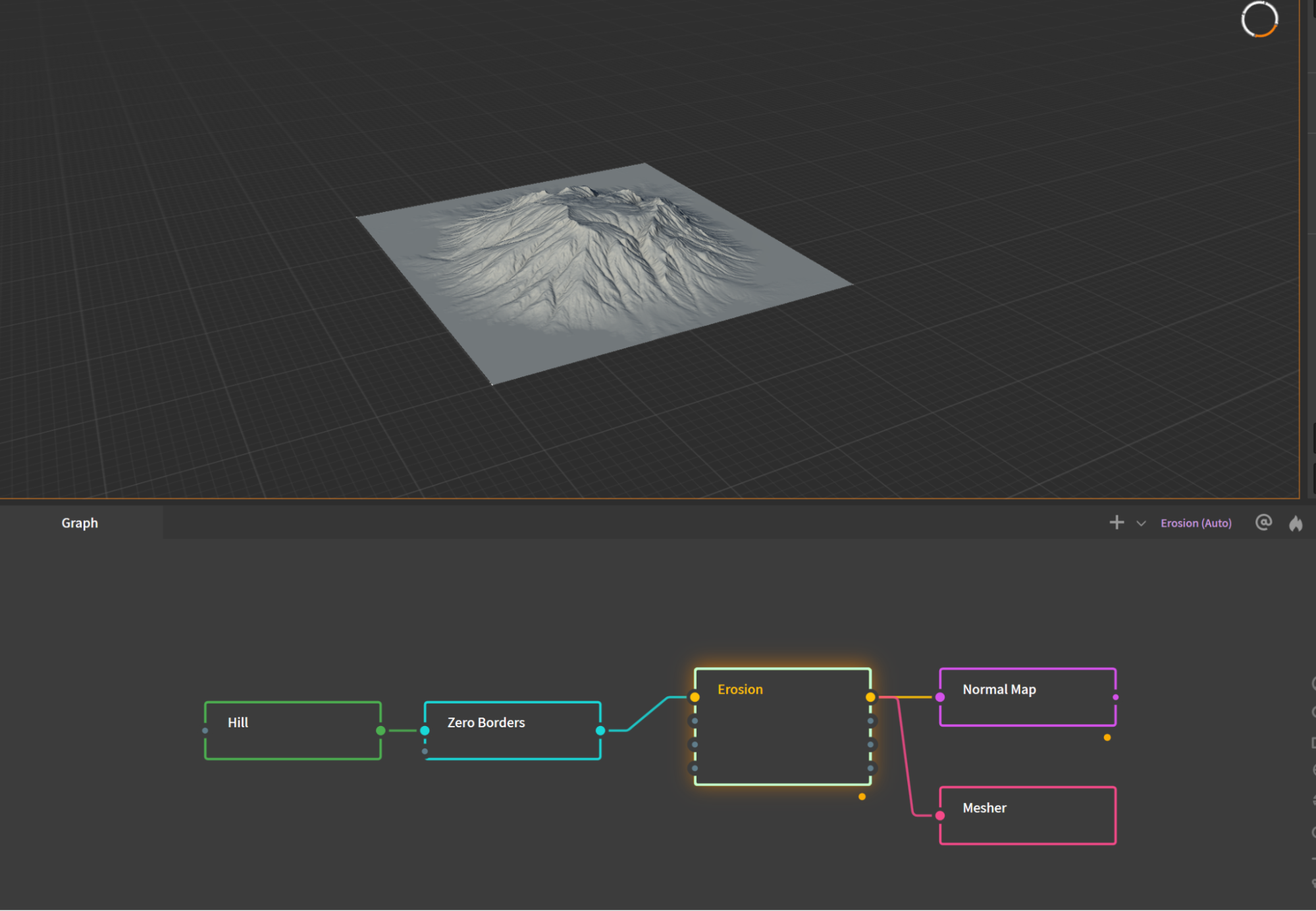

Hills

This one is more of a strategy-specific tip, but to break up a flat part of the map you can use whatever terrain software you have to generate a bunch of low-poly hill meshes and their normal maps, and paint those in the flat part. For instance, here's how you'd do it in Gaea.

Then your material in the game can use a runtime virtual texture (or your engine's equivalent) to reuse the same material from your landscape but with the normal map you generated. I blended it here using the pixel depth offset, so that the edge of the mesh doesn't stand out where it juts into the terrain.